The Zapruder Film: The Most Famous Home Movie that Almost Didn't Exist

And the story of the man behind the camera...

Zapruder was never meant to be a household name and his famous film of the assassination of John F Kennedy almost didn’t exist. Abraham Zapruder had actually left his 8mm Bell & Howell home movie camera behind when he went to work on the morning of November 22, 1963, having given up on the idea of filming the presidential motorcade due to rain. If he hadn’t gone back for the camera at the behest of his assistant, investigators and historians would be without the most complete footage of the events in Dealey Plaza that day.

Today, sixty years on from the assassination that shook the world and spawned dozens of conspiracy theories, it seems that every moment of our lives is filmed and live streamed. If, God forbid, such a terrible event was to occur today, there would be hundreds and hundreds of videos to pour over from mobile phones throughout the crowd.

That wasn’t the case in 1963.

Instead, the only complete footage of the assassination was from Abraham Zapruder’s 8mm home movie camera.

But who was Zapruder?

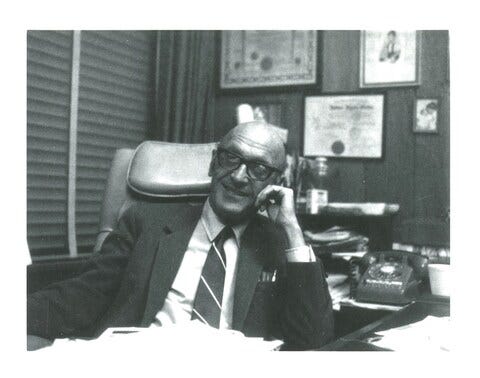

He wasn’t a journalist or a professional filmmaker — instead, he was a businessman, a self taught pianist who never had a lesson, a husband, and a father.

Born in 1905 in a part of the Russian empire that is now Ukraine, Zapruder received only four years of formal education. But that didn’t stop him from making a success of life in America after he immigrated in 1920 to join his father, who had left for America in 1909. He moved into a tenement in Brooklyn, with fellow Jewish immigrants for neighbors. Young Zapruder worked as a pattern cutter in the garment industry by day and studied English by night.

In 1933, he married Lillian Sapovnik and they had two children together — a son, Harry, who graduated from Harvard Law in 1962, and a daughter, Myrna, who volunteered for John F Kennedy’s campaign in 1960.

Abe Zapruder was working his way up the ranks in the clothing industry and in 1941 he was invited to move to Dallas to become an executive at Nardis, a sportswear company.

But Zapruder wanted more. In 1949, he started a company of his own, co-founding Jennifer Juniors, which made clothing for young ladies under its own brand and as Chalet of Dallas.

Their designs were often advertised in Jewish magazines, especially around holidays. Occasionally, examples appear on sites like Etsy, with the purchasers often ignorant of the connection between the vintage dresses and the man who filmed Kennedy’s assassination.

Abe Zapruder had a long love making home movies, long before it was popular. He purchased his first camera in the 1930s, and enjoyed filming various parts of his life.

Below, you can see the Zapruders as Abe proudly holds up his brand new camera — the one that would make him a household name.

By 1963, Jennifer Juniors was based out of the Dal-Tex building, right across the street from the now-infamous Texas School book depository.

Zapruder was a big fan of Kennedy, and, like much of Dallas, was looking forward to the presidential visit. Knowing that the presidental motorcade would pass by the plaza outside his office, Zapruder planned to film the president and first lady — and, as a dressmaker, he was certainly very interested to see what Jacqueline Kennedy would be wearing in Dallas.

But the day of, the weather threatened rain and Zapruder left his camera at home. His assistant, Lillian Rodgers, was disappointed, insisting, “You’re the one who has been making home movies for years, you have to go home and get your camera.”

He listened.

In Dealey Plaza, Zapruder looked for a place to film where he would have an unobstructed view. He finally opted to stand on a concrete pedestal. Zapruder often suffered from dizzy spells, especially when filming with a zoom lens, so he asked his receptionist to stand behind him in case he needed someone to hold onto.

He filmed the President’s car coming down Elm Street and just happened to capture history on 26 seconds of color film.

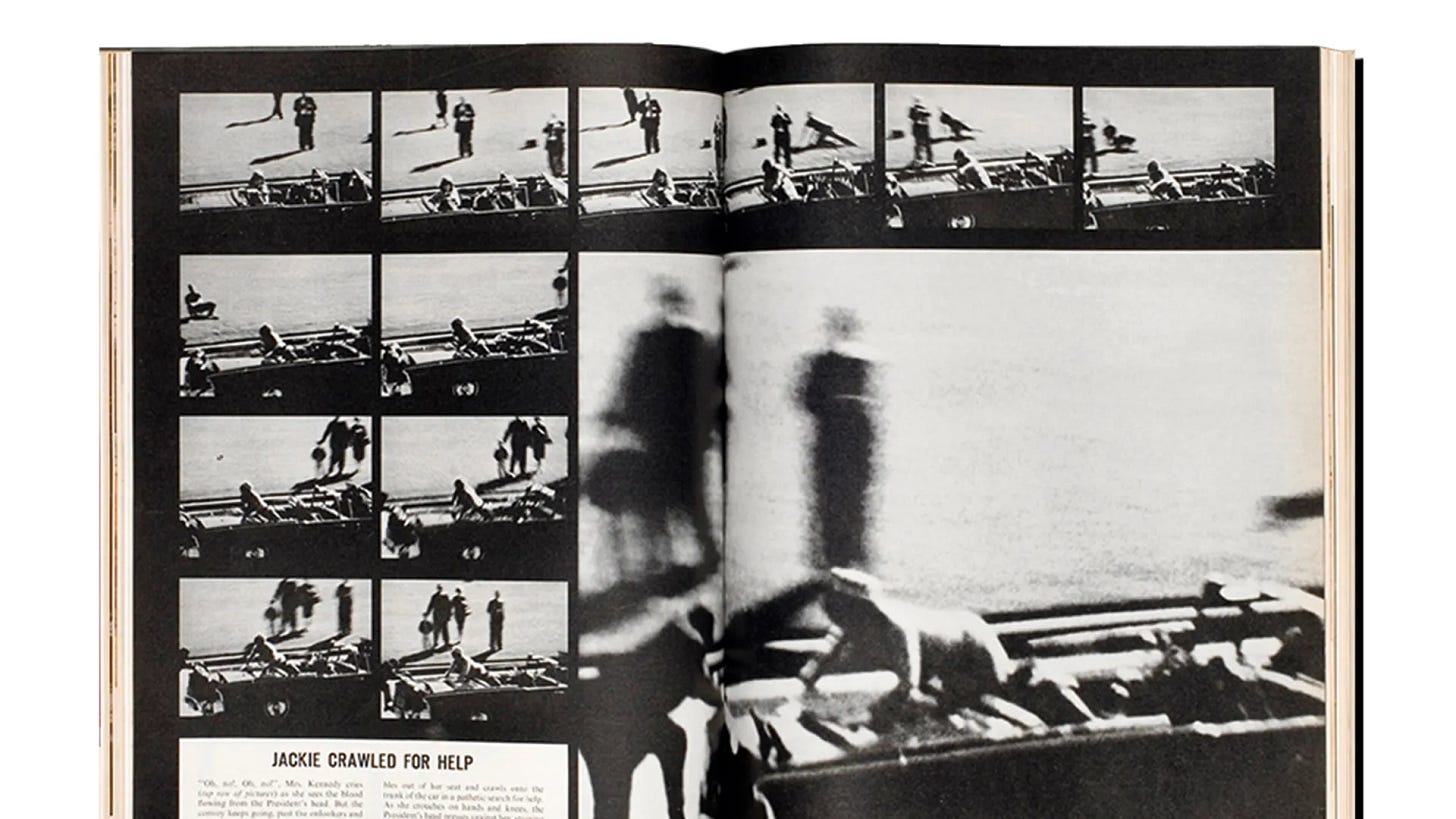

You can see the car disappear behind a sign and remmerge with the president clutching his neck, having been shot. But then frame 313 of film captures the moment when the fatal shot hits Kennedy’s head. Then Mrs. Kennedy reaches for a piece of the President’s skull that had landed on the trunk of the convertible — one of the most famous and heartbreaking images of the events.

The film is below, in its entirety, viewer discretion obviously advised:

Within minutes of the fatal shot, a reporter from the Dallas Times Herald named Darwin Payne found Zapruder and followed him back to his office, where the two men spoke for over an hour. They watched as Walter Cronkite told the country that the President had been shot, but his condition was currently unknown.

Zapruder knew better, insisting, “He’s dead, I know he’s dead, I watched through the viewfinder and I saw his head explode like a firecracker.”

The Secret Service also went to Jennifer Juniors to speak to the man they’d seen with a camera and escort him to the WFAA TV station for the film to be developed. They were unable to do so, but Kodak made two copies: one for the Secret Service and one for the FBI. Zapruder would keep the originally.

Zaptuder was interviewed by WFAA, an ABC news affiliate, on the afternoon of November 22, discussing what he saw and what he filmed:

Of course, the film was indeed developed and screened by the Secret Service. Copies were kept for investigations, and the Zapruder Film, as it has come to be known, was a key piece of evidence for the Warren Comission.

But Zapruder retained the rights to the film. And there was an immediate rush to purchase those rights.

Dick Stolley was a Life magazine editor based out of Los Angeles, but that didn’t stop him from immediately making his way to Dallas to try to buy Zapruder’s footage.

Zapruder knew that the public wanted to see the footage, and several publications offered to purchase it. He had reservations, though, especially after having a nightmare in which the New York Times published a headline enticing the public to “See the President's Head Explode.”

In the end, the rights were sold to the persistent yet polite editor of Life magazine for the amount of $150,000, paid in installment of $25,000. Zapruder donated the first installment to the widow of Dallas police Officer JD Tippet, who was shot and killed when he attempted to apprehend Lee Harvey Oswald.

But Zapruder had conditions for the sale, one of which was that frame 313 would not be published.

As for Zapruder, he never filmed another home movie, stating: “I’m sorry to say I used to be an ardent movie taker and after that tragedy somehow I lost, I don’t know what to call it, appetite or desire to take pictures. I’m sorry, I have beautiful grandchildren growing up, I’d love to take some movies of them. I’ll have to get back to it but somehow I just didn’t have the desire to do so.”

After Zapruder’s death from stomach cancer in 1970, Life magazine returned the rights to his family for $1. The footage would later air in its entirety in 1970, with frame 313 being visible to the public for the first time. Today, it’s been watched by millions.

Further resources:

Thats such an iconic film now. Great dive!