The Rise and Fall of the Biograph Girl — the First Movie Star

The story of Florence Lawrence, from death hoax to stardom to obscurity.

Before there were household names like Clara Bow and Mary Pickford, one silent film actress set the stage for the Hollywood star machine by becoming the first actress in the history of moving pictures to be known by name — a distinction never yet granted to anyone else, male or female.

In a time when films weren’t considered legitimate theatre and movie actors were anonymous, one young woman and her producer utilized what’s now become a time-honored tradition — the publicity stunt — to thrust her into the spotlight and become famous by name.

But how did the first named movie actor in the English-speaking world wind up buried in an unmarked grave in the town that once celebrated her fame?

That’s a long and twisted tale — in other words, it’s Deep Dive History fodder.

The actress later known as Florence Lawrence was born Florence Annie Bridgewood in Ontario, Canada in 1886 — though she would later adjust her age as it suited her. Her father was a carriage builder, originally from England. But it was her mother who had the more interesting career — that of Vaudeville actress. Known on the stage as Lotta Lawrence, Florence’s mother was the leading lady and director of an outfit she called the Lawrence Dramatic Company.

And young Florence followed her mother onto the stage at the tender age of three, singing and dancing alongside her. She started acting in dramatic plays as soon as she could memorize and deliver dialogue. While little Flo enjoyed acting (so long as the material wasn’t too depressing), she wasn’t a fan of life on the road. Nevertheless, her mother promoted her career and she was soon billed as “Baby Flo, the Child Wonder.”

Her parents had been living separately since she was four years old, and her father died in 1898 from a gas leak at his home. At that point, Florence left the theatre company to enroll in school for the first time, returning to the Lawrence Dramatic Company after her high school graduation. But her time with her mother’s company was short-lived, as Lotta soon disbanded it.

In 1906, Florence moved to New York City with her mother, in search of a different dream and a new life — in the motion picture industry. Initially, Florence wanted to star on Broadway and auditioned unsuccessfully before turning to films. There was a lot of money to be made in movies, with a public hungry for the novel medium in any form. But that money didn’t really get passed on to the stars — because there weren’t any.

Studio owners saw that star power and name recognition were a very real factor in the legitimate theatre, but they didn’t view film acting as real acting. And, at a time when motion pictures were so new and audiences would literally go to see anything that moved, there was no need to depend on famous names and faces to draw people to the box office. So they didn’t release the names of the actors who appeared in early films, knowing that the public would flock to see the movies either way.

In December 1906, Florence auditioned for a film role with Edison and got the part because she could ride a horse. She would play Daniel Boone’s daughter in a film called Daniel Boone; or, Pioneer Days in America, in which her mother also had a role. They filmed in freezing weather for about two weeks to earn $5 a day.

In 1907 alone, Florence appeared in thirty-eight films for the Vitagraph Film Company — all uncredited. She also took to the road, performing on stage. This also marked the end of her mother’s stage career, making her last appearance alongside Florence in Melville B. Raymond's Seminary Girls. But Florence still didn’t like what she called the “gypsy life” and returned to New York to make more movies for Vitagraph, where her ability to ride horses secured her more roles.

The pay wasn’t great, and there was no promise of stardom, but it meant a settled life. Between appearing in the films and working as a seamstress as well, Florence was earning $20 a week. And she was getting leading roles — but, more importantly, she caught the eye of D. W. Griffith, a producer-director at Biograph studios who was looking for "a young, beautiful equestrian girl" for his latest film. And he’d spotted Florence and asked around to find out her name. She was able to secure a contract at Biograph for $25 a week, no sewing required.

After starring in The Girl and the Outlaw, Florence continued on at Biograph, still uncredited. Griffith made sixty films in 1908, with Florence appearing in most of them. She also married Harry Stoler, an actor who helped her with her transition to Biograph.

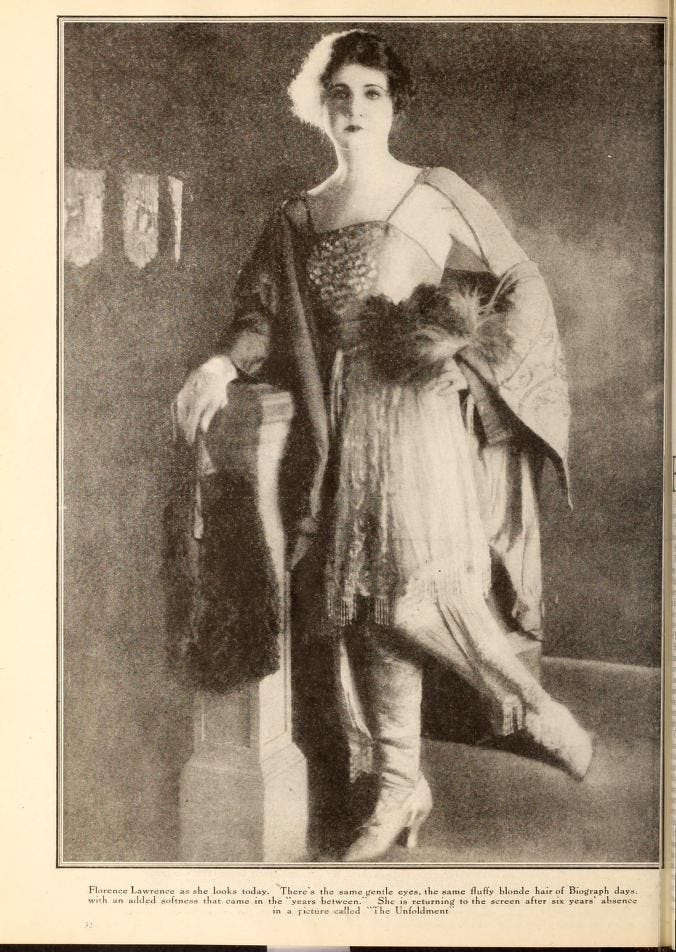

As Florence appeared in more and more films (especially the popular Mr and Mrs Jones comedy series), people became curious about what was quickly becoming a familiar face. But Biograph refused to reveal the name of any of their stars, capitalizing on Florence’s popularity by dubbing her “The Biograph Girl,” a nickname that would later be applied to Mary Pickford after Florence’s departure from Biograph.

Florence and Harry wanted greater success and real fame, so they began to look elsewhere to build their careers in film. They joined Independent Motion Pictures (IMP), which later became part of Universal, after its founder, Carl Laemmle, promised Florence fame by putting her name on the marquee — something that had never been done before. (At least, not in the United States or any other English speaking country. While it was once believed that Florence was the first film actor to be known by name, there is now evidence that French actor Max Linder’s full name appeared on a poster as early as 1907.)

With a glut of motion pictures on the market, it was time for star power to tip the box office scales, and Laemmle had the perfect plan to thrust Florence Lawrence’s name into the spotlight using a publicity stunt in two phases. The first phase was orchestrating reports that Florence, a young actress who appeared in many films, had been hit by a street car and killed. The press ate the tragic story up. Then Laemmle wrote an article of his own to correct the “lie” that his star had been killed when she was alive and well and filming a new movie under her husband’s direction at IMP.

The plan worked.

Everyone was talking about Florence Lawerence, and everyone wanted to see her next film, at least once they saw her in the flesh on her husband’s arm in St. Louis, proving she was indeed alive. The crowd was so excited to see her that they tore at her, ripping the buttons right off her coat. Never one to let an opportunity for more publicity go to waste, Laemmle reported that the crowd had torn her clothes off. Sensational, yes, but it was very effective.

Florence was famous — and that fame was no longer tied to Biograph.

And, for a while, Florence Lawrence was a huge star. She made more than fifty films for IMP before moving on to other production companies.

But entertainment is a fickle industry, and the star machine is always seeking something new.

By the late 1920s, Florence’s star had faded considerably, her career having slowed down before talking films revolutionized the industry. Harry had passed away in 1920 and Florence was on her second marriage, to an automotive salesman. Florence had invented the precursor to modern turn signals as well as a pedal-operated stop sign. But she didn’t patent her inventions and never got any sort of financial compensation for them — nor for the first electric windshield wiper, which she also invented. Her mother tried to get a patent in place but it was too late.

Her mother died suddenly in August 1929, but that wasn’t the end of tragedy for Florence.

Yes, Florence had made a fortune in films, but she’d invested much of that fortune in the stock market, losing in the 1929 crash.

She and her second husband had opened a cosmetics store in Los Angeles that catered to movie actors, but it didn’t weather the economic turmoil at the start of the Great Depression and they closed their doors in 1931 before divorcing the following year.

A third marriage only lasted five months after her husband turned out to be an alcoholic who mistreated her. But that still wasn’t the end of her run of bad luck.

Florence was forced to rely on the small bit of income that she could get from bit parts and work as an extra — and once again, she was uncredited. In 1936, she signed a contract with MGM for $75/week — Louis B Mayer’s going rate for silent era “old timers” he hired for small parts.

But even this wasn’t the end of Florence’s difficulties.

Anemia and depression due to a bone marrow disease was diagnosed in 1937, and the symptoms made it difficult for Florence to work, even as an extra. She kept trying to work, but it was a struggle, and she found herself unable to live alone, moving in with a studio worker named Bob Brinlow and his sister.

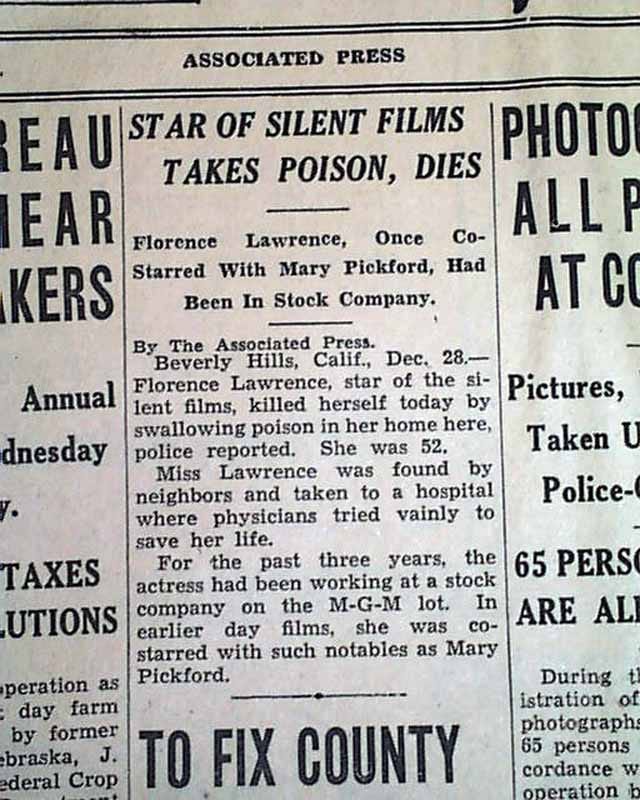

On December 28, 1938, Florence called out from work, saying she wasn’t feeling well. She wrote a note for Bob, which read:

“Dear Bob,

Call Dr. Wilson. I am tired. Hope this works. Good bye, my darling. They can't cure me, so let it go at that.

Lovingly, Florence – P.S. You've all been swell guys. Everything is yours.”

Then, she took a dose of ant poison and cough syrup which would prove fatal, despite the fact that she was alive when she was transported to the hospital.

She died penniless, and the Motion Picture & Television Fund, then headed by fellow Biograph Girl Mary Pickford, paid for her unmarked grave at Hollywood Cemetery (now called Hollywood Forever Cemetery). It wasn’t until 1991 when an anonymous British actor provided the headstone that marks her final resting place today.

Florence Lawerence is no longer a household name — but she paved the way for the star-powered publicity machine that Hollywood became. Her grave near the historic chapel at Hollywood Forever is tended lovingly by silent film fans, and she will always have a place in film history.

Dive Deeper:

Florence Lawrence at Find a Grave

Introducing Florence Lawrence, Hollywood’s Forgotten First Movie Star: Vanity Fair, 2018

Florence Lawrence: Inventor and the World's First Movie Star