The Manilamen of South Louisiana: A Forgotten Legacy

The First Permanent Asian Settlement in the Americas

South Louisiana is known as a rich melting pot of heritage, with a vibrant mix of cultures that is often lovingly compared to pot of gumbo — a staple of Creole and Cajun cuisine that is itself a product of the cultural blend that makes Louisiana, well, Louisiana. But when people discuss the essential blend of influences that shaped the Louisiana we now know, Asian American heritage is rarely listed, lost among the more well-known African and European contributions to the cultural heritage of the region. But there was a Filipino addition to the gumbo pot — figuratively, but quite literally, as well.

In fact, Southern Louisiana was home to the first permanent Asian settlement in the Americas, a fact which few people know. And that’s partly because, as is often the case in a state that’s so frequently besieged by hurricanes and flooding, the settlement itself was washed away and largely forgotten, visible now only in the form of a plaque on the edge of the swamp where a thriving village of Filipino shrimp fishermen once stood.

But why Filipinos? Why Louisiana? And why is this legacy so seldom remembered?

When the first Filipinos came to Louisiana in the mid-18th century, both the Philippines and the Louisiana territory were under the control of Spain. Most everyone in St. Bernard Parish spoke Spanish, which made it fairly simple for Filipinos to live and do business in the region. Some sources say that the village of Saint Malo was founded as early as 1763 by Filipino sailors who deserted from Spanish galleons, while others claim that the village wasn’t established until the early 19th century. And some people say that the Manilamen were the descendants of the Kampangan sailors, whom the Spanish had lent to the French in the 1700s.

Regardless, the village got its name from Jean Saint Malo, who led a band of escaped slaves (also called maroons) and hid out near the Filipino settlement. He was hung for helping them escape slavery in 1784, but the legend of the rebellion he led lived on in the name of the village on the shore of Lake Borgne.

Another Filipino settlement, aptly named Manila Village, was established in Jefferson Parish shortly after the village at Saint Malo, and there were a handful of other Filipino villages in Jefferson and Plaquemines Parishes.

The so-called “Manilamen” got that moniker when they joined the forces of Andrew Jackson in the War of 1812. And, by the end of the war, some of the Manilamen had become US citizens.

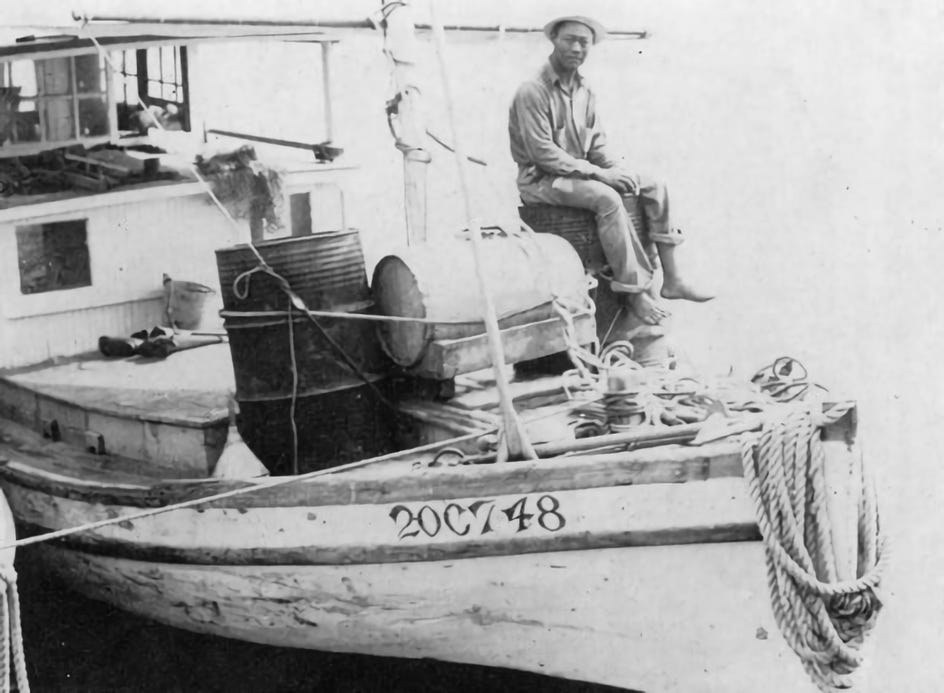

The primary industry of the villages was shrimp fishing, and the Filipino fishermen pioneered the dried shrimp industry. Even today, dried shrimp is a common snack in the region — and a common ingredient in gumbo!

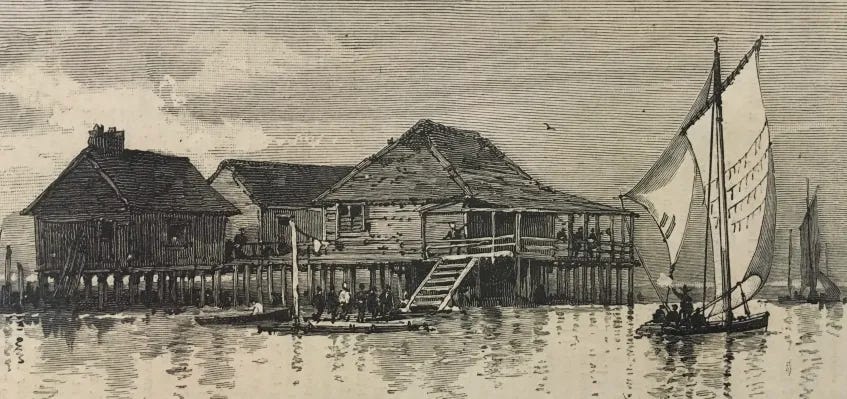

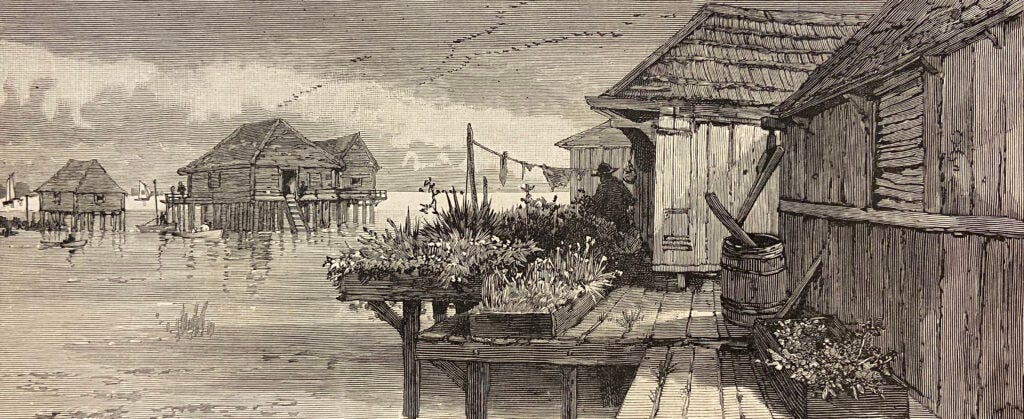

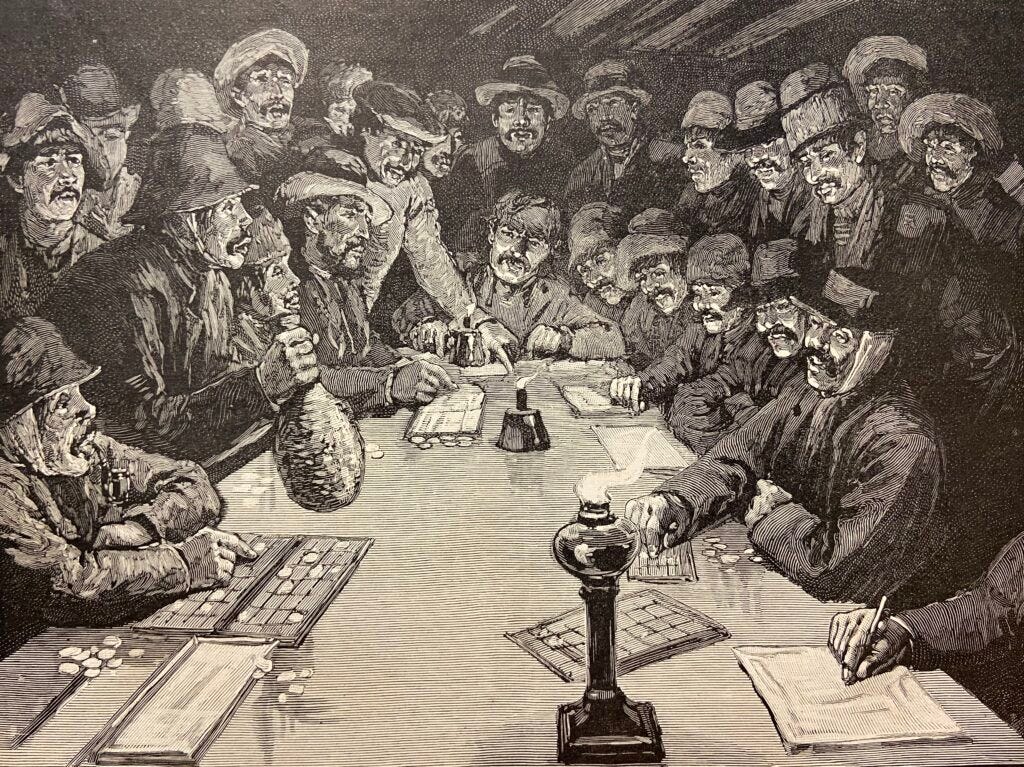

Much of what we know about the day-to-day life of the people of Saint Malo comes from an article written by Lafcadio Hearn for Harper’s Weekly in 1883. This was the first article ever published about Filipino Americans and it was accompanied by several illustrations of the village of Saint Malo and its residents.

The village was made up of little huts, similar in style to those found in the Philippines, but built with local materials like palmetto. Accommodations were Spartan, with simple furniture, such as mattresses stuffed with Spanish moss. Built on stilts on top of the water itself, the homes were vulnerable to storms and changing tides.

There were no Filipino women in the village, and the Filipino men found themselves taking Cajun and Native American wives, most of whom didn’t live in the village, choosing to make their family homes in New Orleans or thereabouts. But many men were unmarried or left the village (and the shrimping industry) to marry.

Saint Malo was set apart from the governance and economy of the rest of the parish and the state, with no government contact — not even from the tax collector. The Manilamen governed themselves, keeping themselves isolated from the outside world — except, of course, to sell their shrimp, which was dried in the sun before being sold in New Orleans.

The village of Saint Malo was destroyed in the 1915 New Orleans Hurricane, and the ruins of the village were abandoned. The residents joined the people of Manila Village, which continued to be an active fishing village until it, too, was destroyed by a hurricane — this time 1965’s infamous Betsy.

Hurricanes have had an effect on Louisiana’s Filipino presence in recent years, too, with Filipino workers coming to the New Orleans area to work in hospitality and healthcare in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. But most of these Filipinos are recent immigrants — and many of them are unaware of the long and rich Filipino history of the region. But that’s starting to change as cultural and historical organizations share the story of the Manilamen and their descendants.

The ruins of Manila Village have receded into the water in recent years, and are now no longer visible even at low tide. And perhaps that’s a metaphor for the Filipino influence on Louisiana culture. It isn’t always apparent, but it’s there, just below the surface.

Dive Deeper:

YouTube: An interview with the descendant of the Manilamen by Kababayan Today

Take Out with Lisa Ling: S1E1 "Mix Mix" on Filipino Louisiana

Atlas Obscura article on Louisiana's Filipino history

October 1587, was when the first Filipinos landed in what is now the Continental United States at Morro Bay.

An hour away from Lompoc you'll find the location commemorating the landing of the first Filipinos in the US.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/First_landing_of_Filipinos_in_the_United_States