The Enduring Fascination of the Amber Room

The restoration, 20 years on, and what (probably) became of the original.

Our collective imagination loves nothing more than a mystery. And there’s nothing like a mysterious disappearance to captivate audiences and spawn books and a multitude of documentaries. And, of course, blog posts.

The Amber Room was an object of fascination even before its disappearance during the Second World War. The warm, golden glow of nearly 1000 pounds of amber in varying shades is a sight to behold and was called “the eighth wonder of the world” even without an element of mystery and tragedy added to the mix.

While the original panels of the Amber Room were never recovered, its modern recreation has been enchanting visitors to the Catherine Palace for twenty years now. In celebration of this 20th- and 21st-century (as such a wonder could never be made in a day or even a decade) resurrection of an 18th-century treasure, let’s dive into the history and the mystery of a Russian icon that had its birth — and, likely, its demise — in Germany.

From the very beginning, the Amber Room was always on the move.

Commissioned in 1701 by Fredrick, the first King of Prussia, the Amber Room was never installed in the palace that was its originally intended home. Fredrick I wanted the room to please his second wife, Sophia Charlotte, and hired German Baroque sculptor Andreas Schlüter to design it and Gottfried Wolfram, master craftsman to the Danish court, to oversee its fabrication. Wolfram, in turn, brought on Ernst Schacht and Gottfried Turau, themselves masters in the art of carving amber from Danzig, in modern-day Poland.

Queen Sophia Charlotte didn’t want to install the room in the Charlottenburg Palace as planned, instead ordering it to be set up in the Berlin City Palace. The opulent room took years to carve and assemble, and when Fredrick I died in 1713, the project was abandoned by his disinterested son, King William Fredrick. But the room’s lack of completion didn’t stop the new Prussian King from showing off the room to Russia’s Tsar, Peter the Great, when he came to visit. The Tsar admired the room greatly and King William Fredrick, eager to please Peter and cement the alliance of Prussia and Russia against Sweden, gave the room to Peter as a gift.

The partially completed Amber Room was packed up into 18 large boxes and sent to Russia, where it was displayed at the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg as part of a collection of European art. Later, Peter the Great’s daughter, Empress Elizabeth, decided to have the room installed in the Catherine Palace in Tsarskoe Selo (now called Pushkin), 19 miles south of St. Petersburg. The then recently constructed Rococo palace served as a summer home for the Imperial family, and the Empress must have foreseen how beautiful the ornate amber-covered panels would look in the glow of the perpetual twilight of St. Petersburg’s famed white nights. The candelabras and the mirrors that reflect their light were a Russian addition to the room, along with four Florentine stone mosaics depicting the five senses that were incorporated into the room.

Various Tsars used the Amber Room for their own purposes. Empress Elizabeth liked to meditate there, while Catherine the Great preferred to host guests in the Amber Room and Tsar Alexander II used it as a trophy room. After the Russian Revolution, the palaces of Tsarskoe Selo became museums, open to the public.

The Catherine Palace was meant to be the Amber Room’s final home, but the Second World War led to its looting and eventual disappearance. In an ultimately futile attempt to preserve the room’s priceless treasure from the invading German army, the Soviets covered the amber panels with wallpaper, hoping to disguise it. They’d already tried to remove the amber panels from the walls, but there was no way to pack the Amber Room away in haste, as the amber, which had been heated and dipped into a combination of linseed oil and honey during the original construction of the room, had grown brittle with age. When the Russians attempted to pry the amber off the walls, it turned to dust. Instead, they settled for disguising it and leaving it to the mercy of the invaders.

Hitler was eager to loot the treasures of every land he invaded, and he considered the Amber Room to be German property, as it had originally been made in Germany. When Tsarskoe Selo was captured by the Germans, the Amber Room was packed up and taken to Königsberg Castle, in East Prussia in October of 1941. Dismantling it took thirty-six hours, with the Wehrmacht soldiers being supervised by two experts.

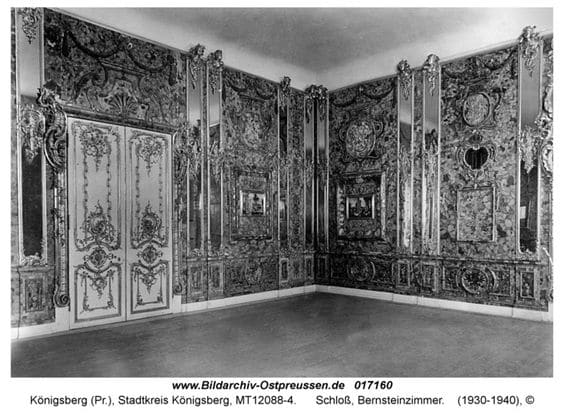

By November, the Amber Room was put on display in Königsberg Castle, and photos from the time show that the panels and mosaics made it to German territory mostly intact, even if they look a bit out of place when paired with a plain plaster ceiling, separated from the Rococo splendor of the Catherine Palace.

But the Amber Room wasn’t to remain in one place for long. As it became evident that Königsberg would not long remain in German hands, the order was given that looted art and artifacts should be removed from the city. That included the Amber Room, which was once again boxed up in 1943. Some eyewitnesses claim to have seen the crates in the basement of the castle as late as January 1945.

From there, the Amber Room’s whereabouts and survival become a matter of speculation, with some witnesses claiming that they saw the crates being loaded onto the Wilhelm Gustloff, a German transport ship used in Operation Hanibal, the evacuation of German troops and civilians from East Prussia and the Baltic. The Wilhelm Gustloff was torpedoed and sunk by a Soviet submarine on 30 January 1945. Divers have searched the debris field in recent years, but no traces of the Amber Room have ever been found amid the wreckage.

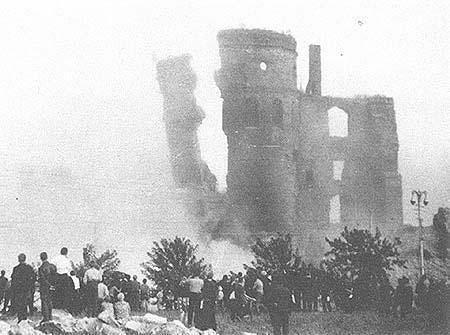

As for Königsberg Castle, RAF bombs in 1944 and a fire during battle in April 1945 left it battered and barely standing. The outer walls of the castle were stabilized later, by the Soviets. Today, Königsberg is part of the Russian Federation, having been renamed Kaliningrad in 1946 after being annexed by the Soviets in April 1945.

In the aftermath of the war, Professor Alexander Brusov was sent to occupied East Prussia to search for the Amber Room and other missing treasures that had been looted by the Nazis. Brusov was a celebrated archeologist, acting on behalf of the Kremlin to determine the fate of the Amber Room. He reported that: "Summarizing all the facts, we can say that the Amber Room was destroyed between 9 and 11 April 1945." In other words, he believed that the Red Army had destroyed the Amber Room along with the castle during the battle. He also claimed to have found the burnt remains of three of the four Florentine mosaics in the basement of Königsberg Castle.

However, the Kremlin didn’t like Brusov’s conclusion — and they hired another expert to mount another investigation. Perhaps the goal was to cover up the fact that the Amber Room’s demise was the result of Soviet actions, or perhaps they were simply motivated by the vain hope of recovering such a priceless treasure. Either way, repeated searches yielded no result.

The most likely scenario is exactly what Brusov determined — the Amber Room was destroyed along with Königsberg Castle. And that’s what British investigative journalists Catherine Scott-Clark and Adrian Levy concluded in their 2004 book, The Amber Room, although their theory is a little different than Brusovs. They believe that the Amber Room was destroyed by the drunken antics of Red Army soldiers, looting their own national treasure as they celebrated victory in the remains of Königsberg Castle.

But that hasn’t stopped various treasure hunters from combing seabeds and searching bunkers and caves in search of the panels and other treasures from the Amber Room. They’ve all been unsuccessful and, at this point, nearly eight decades of suboptimal storage would have almost certainly destroyed the brittle amber and the wood it was mounted on — that is, if it survived the Battle of Königsberg in the first place.

Back at the Catherine Palace, the Germans left behind the shell of a room, and, by the end of the war, the palace that the Amber Room had once called home was a burned-out ruin. Debate about the future of the Imperial Palaces began almost right away, but by the 1950s, work had begun to restore the Catherine Palace to its former glory.

In 1979, the Soviets officially announced their intention to recreate the Amber Room with new materials — an admission that they’d given up any reasonable hope of recovering the original.

A special Amber Workshop was opened in some of the surviving outbuildings of the Catherine Palace, where expert craftsmen were tasked with learning centuries-old techniques that had never been used in Russia — and that were all but lost in Germany and Poland, where they had been originally developed. Pouring over all existing photographs of the Amber Room, they sought to recreate something that none of them had ever laid eyes on, using techniques they’d never tried before. Police forensic equipment was used to determine the exact dimensions of each decorative element in the Amber Room so that the artisans could recreate it. It was a decades-long project, often stalled by various logistical roadblocks and a lack of funds. In the end, the project cost more than $11 million, including $3 million in German donations. The recreated Amber Room required the acquisition of 6 tonnes of Amber in 350 unique shades, 80% of which was waste, and the active phase of the project took 23 years.

And still, despite years of searching, no pieces of the original Amber Room surfaced. At least, until 1997, when one of the stone mosaics, entitled “Smell and Touch” was discovered in the keeping of a notary in Germany, who claimed to have been given it for safekeeping by a German officer who had looted it when the Amber Room was being packed up in Königsberg.

The German government seized it and arranged its return to Russia in 2000, when it was compared to the recreated mosaics in the workshop in Pushkin. The two were virtually identical, which served to silence critics who claimed that there was no way to accurately reproduce the Amber Room based on a few old photographs and the memories of older residents. Returned alongside the mosaic was a small Amber chest of drawers, also looted from the basement of Königsberg Castle. These are the only two elements of the original Amber Room known to have survived.

In June 2003, the recreated Amber Room was unveiled and dedicated as part of the celebrations for the 300th birthday of the city of St. Petersburg, and it has been one of the main draws at the Catherine Palace ever since.

Through the work of the restorers, the rebirth of the Amber Room has also brought about the rediscovery of older techniques of carving and mosaic laying that are lost even in Germany and Italy, where the original Amber Room and the Florentine mosaics that adorned its walls were made. The craftsmen who are still working to restore the palaces of Tsarskoe Selo and beyond have preserved not only the damaged buildings but the technical skills of bygone centuries for a new generation and beyond.

But perhaps the most gratifying part of the opening of the Amber Room to the public was seeing older residents of Pushkin pass through its doors, gazing in awe at a priceless wonder that they’d last laid eyes on as school children, a resurrection of a splendid treasure that is the same in spirit, if not material fact — a hazy memory made real once more, through the tenacity and skill of the artisans who restored it.

Twenty years later, countless people have come to view the reopened Amber Room, finally restored to its former glory. World leaders and celebrities have been rendered speechless by its beauty, and people from all walks of life have been awestruck as they are transported to a different world within its walls.

Far from pretending that the recreated Amber Room is the same as the original, likely lost forever, there is a tangible pride in the decades of effort required for the Amber Room to rise like a phoenix from the ashes of its destruction.

Dive Deeper:

Los Angeles Times article about the rediscovery of the Florentine mosaic, 1997

Vice article about the recreation of the Amber Room

Documentary about the Amber Room Mystery and Reconstruction, via Romanov Royal Martyrs on YouTube

The Official Amber Workshop Website

Review of The Amber Room (2004) by The Guardian

History.co.uk article on the Amber Room and the various investigations into its disappearance

The effects of looting are so interesting. It's good that the two known pieces of the original room were returned (and that they increased opinions on the reproduction!). I wonder which other priceless pieces of art and history are still in people's private collections (possibly without the holder even being aware of the origins after so many years).