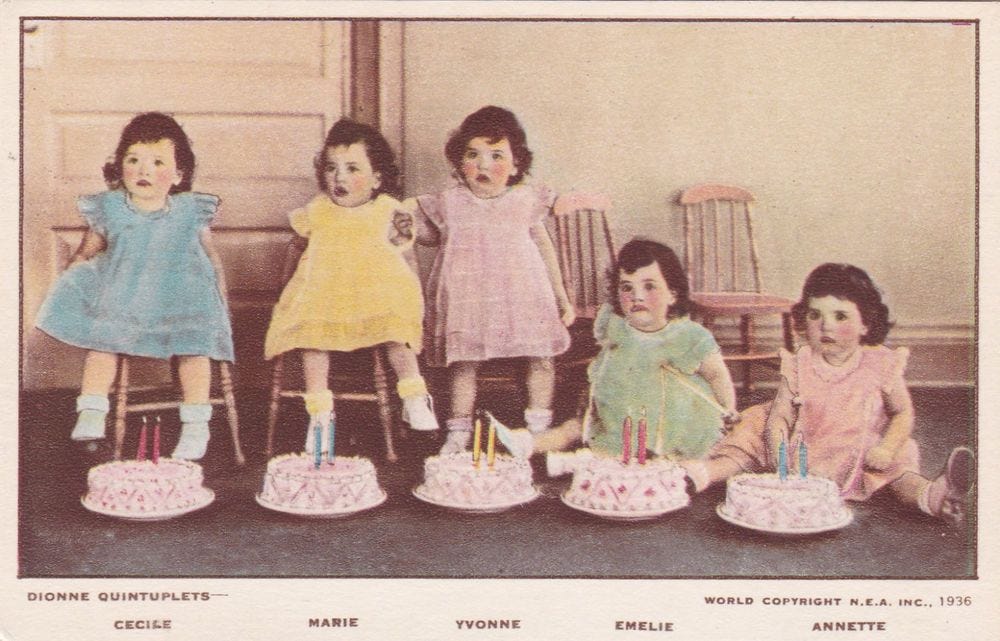

On this day in 1934, Elzire Dionne gave birth to five identical daughters in her farmhouse near Corbeil, Ontario. The miraculous survival of the premature infants became international news, and Yvonne, Annette, Cecile, Emilie, and Marie became a worldwide media sensation. Largely forgotten today, the girls were household names in the 1930s and 40s, a symbol of hope during the Depression and the Second World War.

Today, two of the famous “Quints” survive to celebrate their 90th birthday. While they largely avoid the public eye today, they were once thrust into it, both by the circumstances surrounding their birth and the greed of those around them. Their life stories have always been defined by their survival, but most of their legion of fans never knew the dark reality of the life the world’s most famous little girls endured.

I’ve been fascinated with their story since I was a little girl, although they’re seldom mentioned today — usually coming up only when someone inherits five matching novelty spoons with the images and names of five little girls or five identical baby dolls, each with a different signature color. But two recent books — one fictional and one non-fiction — hope to preserve the legacy of these girls who grew up to warn the world about the dangers of publicizing one’s children.

I grabbed the book on the left off the shelf at Barnes and Noble shortly after its release without even noticing that the author wrote one of my favorite pieces of Romanov fiction (The Lost Crown by Sarah Miller, in case you're wondering.) No, I was busy looking for another book entirely when I saw a book about the Quints and had. to. have. it.

So what's someone under forty doing, grabbing a book on a 1930s-era media frenzy and not only knowing about the Quints but granting them auto-buy status?

First of all, do you know me? I mean, I probably know more about 1930s pop culture than I do about 2020s pop culture. Really. It's what happens when you take an approach to writing historical fiction that borrows a bit from method acting. And when your main babysitters were born in the 1910s.

Secondly, there was this toy in the 1990s called Puppy Surprise and Kitty Surprise. I had both. (And yes, I promise, this is related.) Essentially, was a stuffed animal with a plastic face and a velcro abdominal incision...and you don't know how many babies you'll find until you unbox it and play amateur vet. My Kitty Surprise had 5 babies, and my maternal grandmother exclaimed, "Just like the Quints." Of course, I was a little puzzled. She told me the story of the five French-Canadian sisters born in 1934, but admittedly didn't include the fact that they were kept away from their family and treated like a tourist attraction, at one point boasting more annual visitors than Niagara Falls. Yes, really.

What she probably didn't know is that the girls never felt at home once they were finally returned "home" to their parents and that they even made credible claims of abuse against their father.

I was fascinated by the Quints right away, even buying a tiny set of Quints dolls (made by Tyco and not officially Dionne related) with my allowance. But I didn't know the harder parts of their story until I was an adult. All I knew was that these premature baby girls survived against all odds and became movie stars.

Theirs is a story about the universal appeal of a miracle, and the tragedy of turning five beautiful baby girls into a commodity.

It's a heartbreaking story, and one that we don't see in their three feature films, or in the faces of the (highly collectible) antique doll sets on eBay, or the multitude of posed photos, staged for every season and occasion.

Today, multiple births are, while not the norm, at least not unheard of, either, due largely to the proliferation of certain fertility treatments. But when the five sisters were born, the local doctor didn’t expect them to survive. No set of quintuplets ever had.

In fact, there was no word in French for the phenomenon of five babies born at the same time to the same mother, and the Quints would be known as the “Qinq Jumelles,” or “five twins.” But we’re getting a bit ahead of ourselves.

No one suspected that Elzire Dionne, age twenty-four and already a mother of five, was carrying five more babies. Her pregnancy had been difficult, and the local midwife and doctor suspected that she might have twins — but no one knew that quintuplets were even a possibility. But when Elzire’s labor began early and the young mother’s health wasn’t stable, the midwife sent Oliva Dionne for the doctor.

Doctor Allan Defoe rushed to the Dionne farm, but when he arrived he discovered that the babies had already been delivered by the local midwives. But Dr. Defoe is credited with the survival of the girls — and with participating in the bizarre nature of their upbringing.

The story of the quintuplets was an immediate media sensation — and, in fact, the media played a role in saving the girls’ lives, as it was a reporter from Chicago who helped to locate an incubator that didn’t require electricity, which was crucial because the Dionne farm wasn’t equipt with power.

It was immediately apparent that the girls could earn quite a lot of money for anyone associated with them. Their father was approached by a fair in Chicago with an offer to exhibit the girls in their incubators (something that wasn’t at all unheard of at the time). He signed it on the advice of Dr. Defoe and the local parish priest, but he regretted his decision and tried to have the contract declared void because his wife hadn’t signed it as well. When that failed, Oliva Dionne came to an agreement with the Red Cross that they would have guardianship of the girls for two years, which would put an end to the contract with the Chicago Century of Progress exhibition and provide for all the girls’ considerable medical costs — thus putting an end to the problem that the exhibition money was supposed to solve.

The Red Cross built a hospital across the street from the Dionne’s three-hundred-acre farm — all for the benefit of just five patients. And, at first, it made sense — the girls needed nurses to care for them, and all their needs were multiplied by five. But as they grew stronger and healthier, running and playing like any other little girls, they remained hospitalized, growing closer to the medical staff than to their parents.

The Oliva and Elzire Dionne did a Vaudville stint, capitalizing on the fame that their infant daughters already commanded — but this led to an extension of the guardianship agreement. Between the perception of French Canadians as less educated, anti-Catholic sentiment among those in power, and the public outcry against treating the girls like a commodity, the deck was stacked against the Dionnes. The Dionne Quintuplets Act was pushed through Parliament and made the girls wards of the Crown — an arrangement set to remain in place until they turned eighteen.

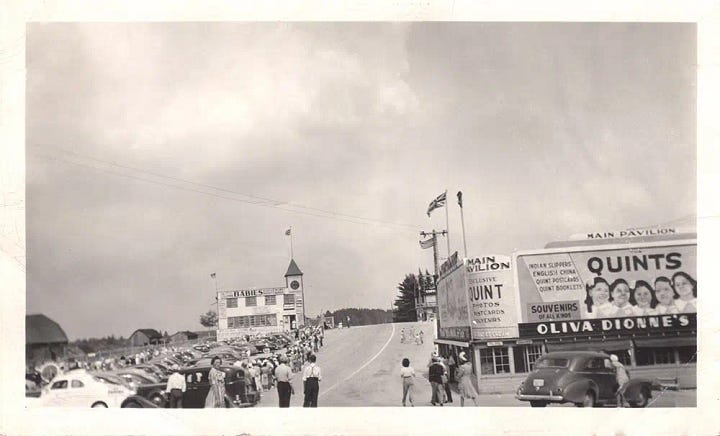

In November of 1934, the girls were taken from their family and raised across the street in the Defoe Hospital and Nursery — a nursery/tourist attraction commonly called Quintland, where the girls grew up in the public eye, as the subject of posed publicity photographs, feature films, and countless pieces of merchandise. In some years, the visitor count at Quintland exceeded that of Niagara Falls.

The girls lived a regimented life on a strict schedule. And all visitors — even celebrities like Clark Gable and Amelia Earhart — were sprayed with disinfectant before being allowed into the nursery, despite the fact that the girls didn’t struggle with ill health.

People traveled great distances to stand in the specially built observation room with screened windows. The tourists could see out, but the girls couldn’t see them — though the girls could hear them during their two to three daily play times in the yard. Merchandise shops cropped up near Quintland selling memorabilia. Women chose rocks and pebbles from the area as “fertility stones” and even Oliva Dionne opened a souvenir shop.

And all those souvenirs made Oliva Dionne quite a bit of money — but not enough to build a larger house near the old farmhouse where his famous daughters had been born. That money would have to come from the trust fund that had been set up to benefit the girls, using the proceeds from their photographs and advertising campaigns. Building “The Big House” was also part of a plan for the Dionnes to campaign for the return of their daughters to their custody.

The Dionnes campaigned publically to regain custody of their daughters, enlisting the help of the Catholic Church and even writing to the Queen. In 1943, the girls moved into the Big House with their parents and eight other siblings. The nursery was converted into a school for the girls, and they finished their education there with high school diplomas in 1952.

But life in the Dionne house wasn't as idyllic as the girls might have hoped. The two groups of children felt like separate families, and the Quints maintained that they were touched inappropriately by their father, coming to dread driving with him. Emilie developed epilepsy after the return to their family, but it wasn’t publicized.

The girls wanted to go their own way as teenagers and adults, with Marie joining a convent shortly after graduation. But she never found peace as a nun — instead, it was Emilie who would spend the rest of her life in a convent.

Emilie passed away in 1954, as a result of her epilepsy, at the convent at the age of just twenty. Photos of her sisters surrounding her open casket would be published — an intrusion on their privacy that the surviving quintuplets were too stunned to object to. Fans flocked to the gravesite as soon as Emilie was buried, taking the flowers from her grave and even plucking up the grass surrounding it, much to the horror of the local parish priest.

The four surviving sisters were forced to begin their adult lives with a missing piece, but they soldiered on. They largely pushed the press away once they recieved their portions of the trust fund at twenty-one, determined to live normal lives. Marie, Annette, and Cecile would go on to marry and have children. Yvonne became a librarian.

Marie would pass away in 1970, of a blood clot to the brain. By the 1990s, both Annette and Cecile were divorced and the three surviving quintuplets were living together near Montreal.

In 1997, following the birth of the McCaughey septuplets, the three surviving Quints spoke out about the trauma and harm that too much publicity can bring. Their parents listened and spared their children from the sort of reality TV spectacle that other large families have endured.

Yvonne died in 2001. The remains of the Quintland building, where tourists peeked at the girls through the screen, was torn down in May 2021.

The two remaining sisters, Annette and Cecile, turn 90 today, away from the public. God knows they've earned it.