Guest Post: Review - Winning Women’s Hearts and Minds: Selling Cold War Culture in the US and USSR

A guest post by Alina Adams

I didn’t write today’s substack. My favorite author from high school did.

Yes, really.

When I met Alina at the Historical Novel Society conference in San Antonio this summer, I would never have thought that she’d offer to do a guest post for my Substack. Heck, I was a starstruck blubbering idiot, so I’m shocked she still speaks to me.

But anyway — here’s Alina with a story that’s near and dear to her heart as an immigrant from Odessa, USSR to the United States.

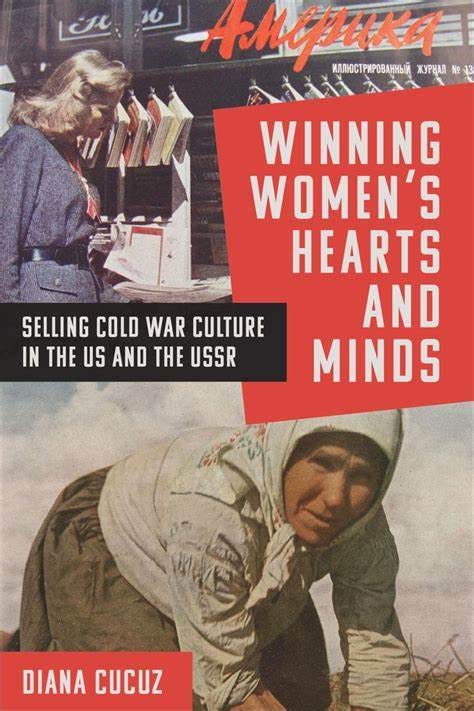

In her January 2023 University of Toronto Press book, Winning Women’s Hearts and Minds: Selling Cold War Culture in the US and USSR, Diana Cucuz, PhD, takes an in-depth look at Amerika, a Russian-language magazine published by the United States Information Agency (USIA) during the height of the Cold War in an unabashed attempt to prove the superiority of the American lifestyle to the Soviet people, primarily women.

As articulated in Amerika’s inaugural issue, 10,000 copies of which were distributed by the US State Department in January 1945: The story we will be telling is the story of the American people. In brief, we shall try to give you a revealing picture of the United States today.

Though the magazine proved to be a success, in July 1952, publication was suspended due to the belief that Voice of America’s radio broadcasts would be a more effective propaganda tool. However, after the death of Josef Stalin, and Nikita Khrushev’s emphasis on cultural exchange in “the spirit of Geneva”, Amerika was revived in 1956, along with the establishment of a mirror-image, USSR, which would be written in English and distributed in the US. It is this period to which Cucuz devotes the majority of her scholarship. (Initially, Amerika subscriptions were to be limited, via an employer or a social or political organization, to “politically literate, ideologically steadfast people,” due to Soviet fears that copies of the magazine might fall into the hands of “the politically immature; Russians who could succumb to Amerika's influence.” In the end, the publication was also available via select public newsstands, where the purchaser could be observed. Rumor had it that many were kept under the counter and sold for far above the printed cover price of five rubles.)

Cucuz sets the stage for how Amerika would opt to frame the lifestyle they were looking to perpetuate abroad by looking to how American women were portrayed in the best-selling US magazine of its day. In Ladies Home Journal, the reader was assumed to be white, middle-class, heterosexual, married, and with small children. While domesticity was prioritized and presented as the ultimate lifestyle goal of any woman, women’s political participation was also encouraged. In fact, anti-Communism was presented as a natural extension of women who “showed allegiance not just to their homes and families, but to their nation.” Women were encouraged to “take active roles in combating the Soviet threat” and “combating Communism by taking an active role in civil life.”

In 1952, the magazine even published an article by a sitting Democratic senator, reminding American women that they had two million more votes than men, and urging them to “Join a Party… Either Party… But Join.” Women were advised that “many public problems are quite similar to housekeeping problems and the housekeeper's viewpoint is essential to their solution.”

Yet, in spite of the periodically activist, pointedly anti-Communist bent, Cucuz holds that “during the early Cold War period… the Ladies Home Journal and Amerika... were used to advertise gender norms and consumer culture to women at home and abroad.”

And it was that consumer culture which was specifically used to highlight “the differences between the two countries, as well as the possible ramifications of communism on any given society. They attempted to show the inadequacies of the Soviet system that deprived women not just of freedom and liberty but also the supposed “special privileges” which American women had, namely the ability to pursue traditional gender roles: to appear feminine, enter into a heterosexual marriage, stay home and care for their families in single-family suburban homes, and fulfill their roles as consumers without the necessity of taking on full-time employment.”

In contrast to the fashionably dressed women gracing the pages of Amerika, Russian women were depicted in articles and photographic essays in the US press as “graceless, shapeless, and sexless.”

Once Amerika was revived in 1956, emphasis was placed on “the concept of freedom of choice in determining one’s role in life. Converting messages about women’s choices was considered especially important because, according to the USA, Russian women lacked the ability to choose their roles in the same way that American women did.”

That choice, according to Amerika, could best be expressed via “fashion and femininity,” “marriage, motherhood and family,” “home and homemaking” and “consumption.”

In 1959, Khrushchev’s “Kitchen Debate” with US President Richard Nixon, where the latter lauded “the convenience of the GE model kitchen, arguing that Americans wanted to make more easy the life of our housewives” while the former noted “that such items were unnecessary in the homes of Russian women because the capitalistic attitude that dictated women should be homemakers rather than workers did not exist under communism” offered the opportunity to wrap all four values into one.

The February 1960 issue of Amerika opened with a photo of Khrushev and Nixon, to make the connection crystal clear, followed by no less than ten articles devoted to the subject of food, including “Easy Cooking in Today’s Kitchen” and a seven page photo essay on the miracles of the modern supermarket. A few months later, the July 1960 featured a multi-color photo spread on a “typical” American kitchen.

As someone who, when my family first moved to America, would leaf through the Consumers Distributing catalog not for the refrigerators and the dining room table sets, but for the glimpses of the food inside those refrigerators and atop those dining room table sets, I can only imagine how photos of conspicuous abundance must have looked to Soviets still living in communal apartments and queuing up daily for whatever groceries they could get their hands on.

“Whether it was food or clothes, Amerika’s’ editors wanted to show Soviet women that it was possible to have options, and these options should include Americanized notions of what was considered acceptable for women. They wanted them to develop a deep dissatisfaction with their lives, as working women unable to care for their families on a full time basis, and for their limited access to consumer goods and services. They wanted them to yearn for another life, one based on the US model.”

It is paragraphs like these that make me wish that the author had devoted as much time to analyzing what Amerika’s sister publication, USSR, highlighted, and what their objective was, in turn.

About 90 percent of Winning Women’s Hearts and Minds focuses on the US perspective.

What we learn about USSR is that “just like Amerika did in its early years, USSR utilized its women to showcase the benefits of the nation…. Russians were encouraged to achieve an aligned life, an ideal form of being that called for individual sacrifice for the sake of the collective, and which was intended to lead to authenticity and meaning.”

But how did this come through in the articles they chose to publish and export? We learn that, in December 1956, readers were let into a “Woman’s Place in Soviet Life.” “It noted the equality that emerged out of the Russian Revolution, the hundreds of thousands of women who held positions in public office and in high level administration, the female factory workers who were ascending into managerial positions, as well as the scientific achievements of women.”

But how did they frame their achievements to make them appealing and even enviable to American women?

USSR did stress that “Russian women had the support of the state; engaged in fulfilling paid labor, and reaped the benefits of socialized daycare to assist them in raising their children.”

Yet “the pages of USSR appeared to corroborate US government and media claims that Russian women’s options were limited.” Even when touting the daycare options available, “women, never men, were shown as the caregivers of small children.” A March 1962 issue devoted to the topic of Soviet women, included a photo series with a scientist caring for his baby while his wife wrote a paper on volcanoes. Nonetheless, the story concluded with the harried father lamenting, “as one man to another, personally, I’d feel happier with a woman in the house.”

What did this say about the image the Soviet Union was voluntarily sending out to the world? Did it speak to a resignation in understanding that the gender equality they touted had yet to pass? The same issue also boasted articles entitled “Spring Fashions” and “Beauty Salon.” Immediately following, fashion became a regular feature of the magazine, though it was categorized under “Miscellaneous.” Was this an admission that, despite earlier denials, the Soviet woman might, in fact, be longing for some of capitalist finery available in America?

If it was, it was far from a full surrender, as the special issue also concluded that “the modern woman (does not) lose any of her feminine graces when she regards just and equal law as more important than serenades and madrigals.”

According to Cucuz, the message designed to be drawn from the above was that “in spite of Western Cold War language that suggested otherwise, the Soviet Union was more democratic than the United States because it provided its women with equal rights rather than the special privileges that emphasized their differences…. Russian women were equal to men in all capacities: in employment, salaries, and education. They were given equal opportunity in all economic, scientific, cultural and political spheres, and an equal right to elect and be elected to public office… (Women’s) outside jobs made a larger social contribution than keeping house or raising children.” (Also, “convenient household items were unnecessary in the home of working Russian women and certain ones even made them lazier.”)

Though “Winning Women’s Hearts and Minds” offers a comprehensive glimpse at what was published by Amerika and the objectives behind each article, I would have loved to read more about how Soviet women reacted to the magazine.

My mother, living in Odessa, USSR, remembers seeing the Elizabeth Taylor movie, Father of the Bride, as a pre-teen, sometime in the late 1950s. In the movie, the eponymous family is considered middle class, with a working father and stay at home mother. Yet they live in a two story home - with a prominent kitchen - own a car, and dress with more variety than the average Soviet bride to be. I asked my mother, “You grew up being told there was no better place than the Soviet Union. That if you thought you were lacking in food and material goods, that meant the rest of the world was much poorer. How could you see a movie like that and believe it?”

“Oh,” she said, “We assumed they were lying. It was like a fairy tale.”

Did the Soviet women who read Amerika during that same time period believe they were lying? And how did the American women reading USSR feel about the oft-repeated complete gender equality on display? Did they think they were lying too?

Winning Women’s Hearts and Minds does an excellent job of detailing what Amerika and, to a lesser extent, USSR’s, objectives were. I’d have loved to hear, straight from the readers themselves, whether or not any were actually accomplished.

Okay, it’s Rose again.

Thank you, Alina, for sharing your thoughts with us.

Reading this review makes me want to pick up a copy of Winning Women’s Hearts and Minds, and also gives me a lot of thoughts about a completely different perspective on the so-called “Mommy Wars.” Even today, we debate which option is more freeing for American mothers: the ability to make one’s primary occupation the raising of children, or the ability to go to work for someone else and have a career. Either way, I’m thankful to be able to sit back and read a book while the laundry and the dishes do themselves. And maybe one of those books will be the one where magazines sold fairytales to Cold War rivals.

I forgot to provide a link to Alina and her daughter discussing this book. You can find it here: https://youtu.be/TDi1g3VSaIA?si=syyL0jOGr8ZnK5uh